Prophetic Reluctance

A general trend exists among the prophets of the Old Testament. Few appear eager or excited about their calling. It’s stunning how predictable this prophetic response is, even if it remains difficult to pin down or unpack. I think, if left to my own instincts, I’d highlight the following prophetic character traits: courageous, empowered, inspired, poetic even suffering. But what about reluctant? It may not appear obvious at first glance, but it’s true. The prophets embrace their calling reluctantly, and they do so, in part, because the prophets understood something about the nature of their calling. Bearing God’s Word is a burden; it’s painful. And the source of the pain is, more often than not, the word of God that they themselves deliver.

Moses, that paradigmatic prophet of prophets (Deut 18:15-20), receives his call from an enflamed bush. I think we can all agree that’s some call, a pretty clear answer to the “what does God want me to do with my life” question. We have fond family memories of our son Jackson requesting “the burning tree” story almost every night when he was younger. And why not? The story ignites the imagination. Think of the artwork inspired by the scene. Marc Chagall’s painting, “Moses Before the Burning Bush,” springs to mind. Chagall depicts Moses aglow before the luminous tree while the Tetragrammaton makes his appearance known. It’s in the midst of this wonder where a type or prophetic pattern emerges. Moses hesitates before God’s call. He’s reluctant. “You know, I’ve never been good at public speaking.”

Isaiah withers in God’s exalted presence: “Woe is me.” After his cleansing, Isaiah offers himself as the Lord’s spokesman and representative. In what appears a bait and switch move, Isaiah signs the prophetic contract, so to speak, before he learns the terms of the call or recommission. “Your word, Isaiah, will be the means of my deafening the ears and blinding the eyes of my people.” In short, Isaiah, your prophetic call entails a ministry of judgment. Now, Isaiah hesitates. After hearing the terms of the call, he asks the martyr’s question. “How long, O, Lord?” Yes, indeed, how long? Amos reveals his own self-awareness: “I’m not a prophet, neither the son of a prophet.” Micah announces ruin to the cities of Judah’s lowlands in Micah 1, only to conclude the chapter with a dirge about his own suffering and loss in the midst of this judgment. Alert and empathetic readers struggle to read the prophets without some deep sighing. Little wonder the prophets were reluctant. Hosea, how’s your wife doing?

Jeremiah’s Prophetic Burden

Among the prophetic choir, one sufferer sings an especially woeful tune. When called, he too recoiled at his vocational prospects. “I’m just a young man, Lord.” Nevertheless, the Lord lays a heavy burden on this young prophet-priest from Anathoth. “Jeremiah, you’ll do what I tell you to do.” God appears to have forgotten his velvet gloves in Jeremiah 1. And if you’re wondering where Anathoth is, think single traffic light, RC Cola and Moon Pie kind of towns, not bustling metropolitans. In other words, Jeremiah was out of his league in Jerusalem, just the way God often likes his spokespersons.

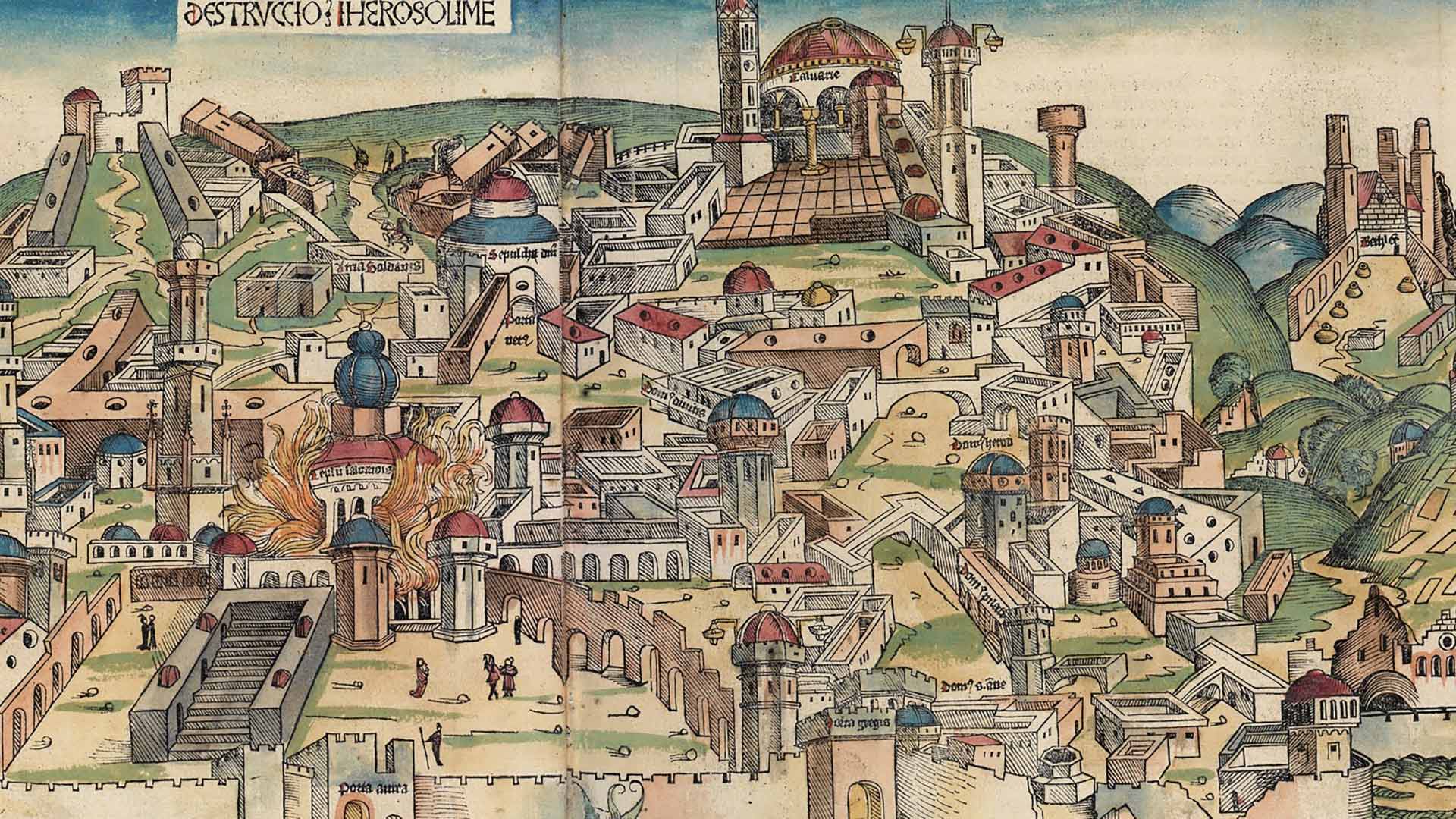

Jeremiah, like the prophets before him, had a penchant for igniting the wrong people. When he preaches what appears to be one of his “favorite” sermons in chapter 26, let’s just say the response from the hearers wasn’t a handshake and a “nice sermon, pastor.” What Jeremiah says in this sermon shocks and stuns. He pulls no punches, leaning into what must have been the most controversial thing a prophet could possibly say in pre-exilic Judah. I’ll paraphrase. “If you don’t amend your ways, pay heed to my instruction, and listen to my word, then this temple of yours will become a faint memory. Don’t trust in this temple as if it’s indestructible. Because it isn’t. If you don’t think this is possible, then recall what the Lord did at Shiloh.” Jeremiah said something almost verbatim in his first temple sermon (7:1-34), drawing out more fully the Shiloh analogy. The Lord first gave his name, his presence, his very being to dwell at Shiloh, yet, in time, this sacred place became the location of idolatry and covenant infidelity of the worst kind. In effect, Jeremiah says, “Go visit the tabernacle in Shiloh. When you arrive, it won’t be there because God reigned his judgment down on the place. It happened there; it can happen here.” Jeremiah’s homily is terse and direct. No one left the sermon perplexed at its meaning or sorting out hidden innuendos. Repent or Zion as you know it is over. What was the response from the prophets and priests, Zion’s principal stakeholders? Canon fire.

The scene unravels and grows chaotic. The stakes for Jeremiah were very high at this point. The priests and prophets seize him and sentence him to death. To describe the reaction of the religious elites as “vitriolic” appears understated. They were incensed to murder because Jeremiah spoke against their religious symbol and raised questions about the inviolability of Mount Zion. Haven’t you read Psalm 46, Jeremiah? Zion cannot be shaken! And Jeremiah’s entire prophetic ministry challenges this theological one-sidedness with a courageous and burdensome prophetic response. Haven’t you read the book of Deuteronomy, Jeremiah retorts? When covenant loyalty to the Lord elides into religious platitudes and tired slogans—The Temple of the Lord, The Temple of the Lord, The Temple of the Lord this is (7:4)—then Zion would do well to recall the story of Shiloh. Do you understand what I’m saying, prophets and priests? Apparently, they did, because Jeremiah now finds himself sentenced to death.

The burden of Jeremiah’s ministry reverberates off the prophetic page. Threatened with impending death, Jeremiah stands in need of a lifeline, an advocate who can mitigate the charges leveled against him. Who will step into this perilous scene to rescue Jeremiah? Enter stage right: the prophet Micah. The officials overseeing Jeremiah’s hearing appeal to Micah in defense of the hard word Jeremiah delivers. Didn’t Micah say something similar in the days of Hezekiah? Micah, like Jeremiah, did not hail from the urban center but came from the lowland regions of the Shephelah. And, like Jeremiah, he speaks a word of judgment against Zion in the face of her covenant faithlessness and injustice. “Zion shall be plowed as a field” (Mic 3:12). The officials, therefore, at Jeremiah’s trial defend him, with Micah coming to Jeremiah’s rescue. Crisis averted.

Prophetic Hope

Jeremiah and Micah share some canonical affinity for one another. They level claims against the abuses and faithlessness of the religious and political classes, sharing much of their prophetic substance in common. As stated above, Micah 3:12 appears as a quoted text in Jeremiah. While prophetic allusions and echoes abound in the prophets—e.g., Isaiah 2 and Micah 4 are almost carbon copies—actual quotations attributed to a particular prophet do not. Believe it or not, a direct quotation of another prophet is a rarity. Actually, “rarity” is the wrong term. It only happens here in Jeremiah. All the more curious is the text quoted: Micah 3:12. Here’s where things get interesting and encouraging.

Micah 3:12 sits at the exact middle point of the Minor Prophets or the Book of the Twelve. Leaving the textual details to the side, Micah 3:12 and Micah 4:1 form something like the center crease of the Minor Prophets, Hosea through Malachi. If your copy of the Minor Prophets fell open naturally to its center point, you’d find yourself at this textual juncture. In a nice turn of phrase, Christopher Seitz identifies Micah 3:12 as the Good Friday of the Minor Prophets. The imagery leaves little to the imagination: Zion plowed like a field; Jerusalem a heap of ruins, a pile of rubble for future archaeologists to rummage through. Micah 3:12 speaks of death. Yet, Micah 4:1 bursts forth into life and light, Easter Sunday if you will. “It shall come to pass in the latter days that the mountain of the house of the Lord shall be established as the highest of the mountains” (Mic 4:1). The character of God emerges at this juncture as the one who can both put to death and bring to life. The Triune God of the Bible takes dead things and raises them up again: Israel from Egypt; Zion from the rubble; Jesus from the grave. Both Jeremiah and Micah share in the same prophetic hope: the character of God to judge and to make alive.

Conclusion

The prophets offer little in the way of solace for ministers who suffer under the burden of their ministries, at least in terms of a get-out-of-jail-free card. Jeremiah’s prophetic legacy gives no comforting hug for those weighed down by God’s Word or laboring in difficult circumstances. What would Jeremiah’s counsel be? Just hang in there, friends; the prophets and priests probably won’t kill you…maybe. What we learn from the prophets is their own solidarity of living into the challenges of their moment, challenges brought on by sin and the judgment of God’s Word. Jeremiah teaches us the promises of God “to be with you to deliver you” in those Red Sea moments. The prophets remind us of our heavenly citizenship and our loyalty to a King who reigns above all earthly powers and kingdoms. Why in the world would ministers find any of this comforting? Because God’s character is trustworthy and in these matters of life and death, somewhat predictable. Our Father takes dead things and makes them alive again. He takes plowed Zion and raises it as the highest of all mountains. We find comfort and solidarity with the prophets because, like them, we put all of our hope and trust in a simple prophetic phrase: “In the latter days.” Or in terms of our Christian confession of faith, “I believe in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.”

Listen to a Conversation with Mark Gignilliat

Mark Gignilliat is professor of divinity at Beeson Divinity School, where he teaches Old Testament and Hebrew. He is the author of Reading Scripture Canonically: Theological Instincts for Old Testament Interpretation and Micah: An International Theological Commentary.