More than 60 administrators and teachers from 22 schools throughout Alabama came to Samford University last week to discuss how to give students a moral compass to match their academic achievement.

Samford’s Frances Marlin Mann Center for Ethics and Leadership and Orlean Bullard Beeson School of Education hosted a Character Education Workshop June 18-19.

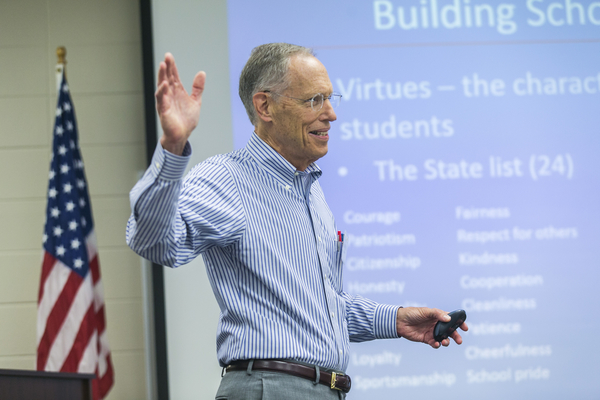

Drayton Nabers, Jr., director of the Mann Center and the driving force behind the workshop, said schools have been distracted by an emphasis on students “becoming smart” at the expense of character development. He said the result is that many people with every advantage have “squandered their intelligence” because they lack character.

Nabers formerly was finance director for the state of Alabama, Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court and CEO of Protective Life Corporation. He also is chairman of the board for Cornerstone Schools of Alabama and author of The Case for Character and The Hidden Key to Happiness. Character education is his passion but also his frustration as he sees the failure of institutions that once shared this responsibility.

“Family is the chief incubator of character,” Nabers said, adding that in many cases family has broken down. He observed that churches, too, often lack the resources or opportunities to ensure that new generations understand and value good personal character. Whether public or private, Nabers said, “school is where it has to get done.”

Nabers said schools must make character education an explicit part of their missions and develop the culture that will allow it to succeed. That means building support among top leaders, teachers, parents and students.

Featured speakers Amy Johnston and David Keller helped participants plan for the daunting task of building successful character education programs in their schools. For much of the first day of the workshop, they described in detail the “11 Principles of Effective Character Education” developed by character.org.

Keller, director of strategic initiatives for that organization, previously served as Deputy Vice Commandant at the United States Air Force Academy, where he led cadet character, ethics and leadership programs. He said the 11 Principles are guidelines rather than rules because every school culture is different. Workshop participants must do the very hard work of building programs that work for their own students. “The most important thing they need to understand is that it’s a process,” he said. Those who take up the challenge have “the freedom to fail, freedom to try and the freedom to have uncomfortable conversations,” Keller added.

Johnston, interim principal of First Baptist Christian Academy in O’Fallon, Missouri, and a consultant for character.org also emphasized how important it is for the adults in a school to have those tough discussions as they evaluate themselves as character models. “These conversations will cause civil war… have them,” she said.

Johnston’s straight talk, informed by three decades in the trenches of character education, clearly resonated with workshop participants, as when she lamented that “technology has replaced relationships.” There is no “app” for the kind of change she has led in Missouri, where she earned the St. Louis Area Middle School Principal of the Year Award, the University of Missouri-St. Louis Dean’s Award for Excellence in Character Education and the Dean’s Award for Excellence in Education Leadership. For all the apparent convenience that technology offers schools, she said, students “see enough adults with their faces in a device,” and might get more out of a simple conversation.

Keller said the potential benefits for students, schools and society are worth the temporary discomfort, demanding work and genuine relationship-building. He said making character education the explicit mission of a school helps prevent derailment by “the tyranny of the urgent” and emphasizes that character education is not a passing fad. “It isn’t one more thing you do,” he said. “It’s how you do everything.”