Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Taylor Branch painted a graphic picture of the segregated South of the 1950s for a Samford University audience that was largely college-aged, and said the key to breaking down that structure was provided by the African American high school students of Birmingham.

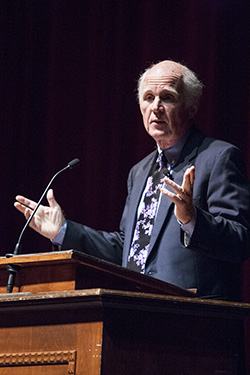

Branch, who wrote the award-winning biography of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., delivered Samford's annual J. Roderick Davis Lecture Oct. 16 to a crowd of about 1,000 in Wright Center on the campus.

He asked the students to imagine a South that had no black athletes, no professional sports teams, and one in which women "were back in the kitchen" unable to serve on juries and in many cases not registered to vote. Not all universities accepted women, and those women that worked filled secretarial, nursing and teaching roles only, he said.

"The thought of women at West Point or the service academies was beyond your wildest dream," he added.

"This was a different world," he said. The segregation of whites and blacks "was personified in racial laws. You couldn't play checkers," and the separation was enshrined in city codes.

"This was Alabama and the South in the 1950s," he said. "That's how I grew up" in Atlanta, Ga.

King had fought segregation for several years when he came to Birmingham in 1963, but the system was as strong as ever. "Not a single public official across the South had advocated the end of segregation laws," said Branch. The Civil Rights movement was losing momentum.

"King's letter from Birmingham jail drew a great yawn across the country," said Branch. "What charged the movement were the high school students that were willing to march" in the Birmingham demonstrations of May 1963.

The parents of the students were fearful for their safety in the face of Birmingham's segregationist police commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor, but the students marched anyway. When the nation saw "kids marching against dogs and fire hoses," President John Kennedy was forced to initiate some action against segregation laws.

"The breakthrough in Birmingham changed the conditions of segregation" and other forms of discrimination, said Branch. "We are the beneficiaries of that nonviolent protest."

Branch said he became interested in writing about King and his movement during his childhood and college days. His father, Franklin Branch, a 1943 Samford graduate, owned a dry-cleaning business and had a close friend, Peter Mitchell, that worked with him. Mitchell was African American, but the two were close and enjoyed each other's company.

"They had to be careful when they went to an Atlanta Crackers baseball game, where they sat in separate sections," said Branch. "My earliest political memory was hearing my father say, 'I don't like this.'"

Branch said his study of King taught him about hope, and quoted King as saying, "What is democracy but a cathedral of hope." Branch said Birmingham's past "was a key to hope for America."

Branch won the Pulitzer Prize for his 1989 volume on King, Parting the Waters. His trilogy on the civil rights leader also includes Pillar of Fire and At Canaan's Edge. "They are long," he admitted, "but I wanted to do some story-telling in the books, to make them human."

Video: Comments from Taylor Branch