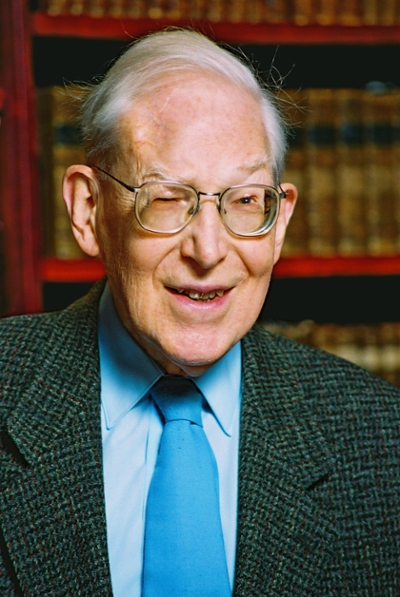

J. I. Packer, also known as Jim, went to be with the Lord on July 17, 2020. Jim was a founding member of Beeson Divinity School’s Advisory Board in 2012, and delivered Beeson Divinity School’s annual Reformation Heritage Lectures in 1994. In 2012, Beeson hosted a conference in honor of Jim called, “J. I. Packer and the Evangelical Future,” which produced an edited volume overseen by Founding Dean Timothy George. The following is a tribute to Jim, who was a longtime friend of George.

I first met Jim Packer when I was a student at Harvard, and he came to Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, which is not far from Harvard, for a conference on the Bible. In those days, I would go up there often for different kinds of conferences, and that’s where I met Jim. At that time, I didn’t get to know him really well, but I was very impressed with him. I was impressed with how he spoke, how he thought, how he organized his material, and the content of what he said. He struck me as a person who was a genuine intellectual as well as a deeply committed person of the church. He also had a deep spiritual center to him beyond that of typical scholars I knew in those days.

When I came to Beeson in 1988, Jim was one of the people high on my list to invite to come and speak at Beeson. He came to Beeson very early: to teach at our Pastors’ School, to give lectures, and to participate in various consultations. I got to know him as a scholar, writer, teacher of the church, and a person deeply concerned about theology and spirituality.

Jim was a pioneer in the work of Evangelicals and Catholics Together (ECT). He was an original signatory. It was through Chuck Colson, who knew Jim well and had great esteem for him, that I became further acquainted with Jim. Both Chuck and Richard John Neuhaus invited me to become a part of ECT after that first meeting. ECT had two senior leaders at that time: on the Catholic side Cardinal Avery Dulles and on the evangelical side Jim Packer. We began working together leading discussions and drafting statements. Jim and I worked together closely and became very good friends.

Also, at the same time as ECT was unfolding in the early 90s, Jim and I were working together at Christianity Today (CT). In those days, Jim and I would go to CT three to four times each year for working sessions with the staff on various theological issues. We were called senior editors in those days: Jim Packer, Tom Oden, and I—an Anglican, a Methodist, and a Baptist. We got along well together. We didn’t agree on everything, but we agreed on a lot of things. We developed a common voice, speaking to many issues and giving guidance when we were asked to do so. These opportunities propelled us into other venues as well: Wheaton College, the Evangelical Theological Society (ETS), and Prison Fellowship.

Another point of interaction was the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA). In those days, they were planning the big Amsterdam 2000 Conference. Jim was the chair of the theological track, and I was his co-chair. This track included all those involved in theological education out of about 13,000 delegates from more than 200 countries who came to the conference. He asked me to chair the committee that would draft the Amsterdam Declaration. I was the principal drafter and oversaw the committee, which also included Beeson faculty member Frank Thielman, with Jim giving overall guidance.

It seemed natural when we started the Advisory Board in 2012 to ask Jim to serve on it. Chuck was also a member of the original advisory committee. As I think about Jim’s overall influence on Beeson Divinity, I remember him as a mentor and an encourager to all of us. Like his Regent colleague James Houston, who had a special relationship with Beeson, both he and Jim emphasized the coinherence of theology and spirituality. They were very similar in that they both expressed the importance of theology being a matter of the heart as well as the mind. This was an emphasis they brought and incarnated in many ways.

Jim also was a great encourager to me personally. Jim represented a special kind of Anglican evangelicalism. He was an ordained minister in the Church of England, a committed Anglican but an evangelical Anglican. He represented that tradition of the church in a way that really connected to me and had a great influence on Beeson. Along with that focus, I resonated deeply with his ecumenical concerns. I had already developed some of those concerns from my great teacher at Harvard, George Huntston Williams, but Jim fostered those concerns further. Jim and I made a good team working together on Christian unity. Clearly ECT was the primary place we did that, but in other venues, too, we tried to advance the ecumenical cause from a biblical and evangelical point of view.

What did I learn from Jim Packer about Christian unity? This: Jesus thought it was important and so should we. Jim approached Christian unity in two ways. First, in all my many, many hours of conversation with Jim around tables at ECT and elsewhere, he came across as a person of deep conviction. I would aspire to be that myself. He was not trying to make ecumenism political; he knew that Christian unity was not about hedging, trimming and coming up with the lowest common denominator. That was never Jim Packer’s approach. Instead, he said: let’s drill down to the core reality of Christian faith in each of our traditions because we believe there is a common root in the Scriptures and the historic Christian faith. Let’s see how far down we can go to see how it opens up a channel of unity. That was his approach. Secondly, the way he could carry on serious theological discussion in an irenic way is something I aspire to. I never saw Jim get mad. I did see him get frustrated, but he never lost his temper. He was always trying to recognize that the other person may have a point. So I need to listen as well as talk. I need to learn as well as share. That was Jim Packer’s approach. I saw him model this time and again and do it very effectively. I hope some of that rubbed off on me a little bit.

Jim lived in the light of eternity, and he knew he was headed there. He talked about this in his later years when he couldn’t travel, and his eyesight failed. The times we were together, or when we would speak on the telephone, he always revealed a sense of eternity about him—that this world is not our final resting place, that we are pilgrims headed somewhere. I’m going to miss that camaraderie around the pilgrimage. I look forward to seeing him in heaven because I believe he is there. He’s at a resting place that he’s longed for a long time. He lived with heaven in view. As someone said of George Herbert after he died: “Heaven was in him before he was in heaven.” That’s a good lesson he leaves for all Christians who follow.

Timothy George is distinguished professor of divinity at Beeson Divinity School, where he served as founding dean from 1988-2019.