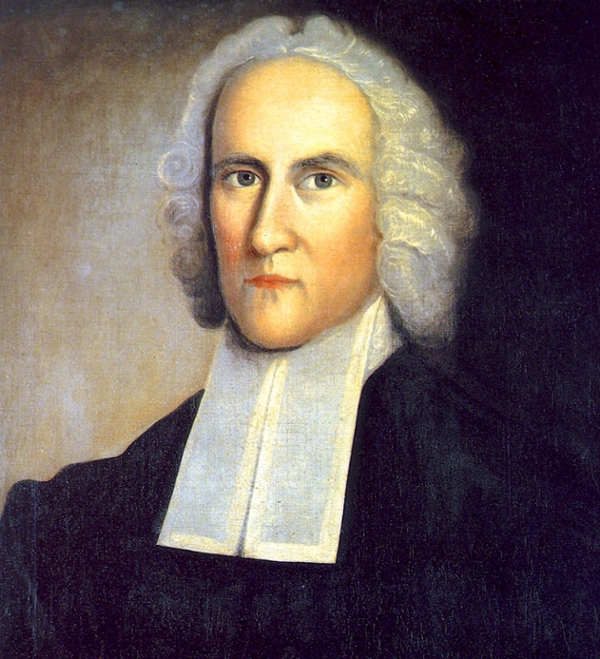

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) is the most influential thinker in all of evangelical history. He worked as a parish pastor, missionary, and college teacher. He mentored younger pastors and he published many books. By the time that he had died, at the age of 54, he had sparked a new movement of Reformed evangelicals who played a major role in fueling the rise of modern missions, preaching revivals far and wide, and wielding the cutting edge of American theology. Edwards’ works are read today on every continent in the world (except Antarctica, of course). He has never gone out of print. Younger Christians, in particular, continue to flock to seminars and conferences on him.

I have written and spoken on Edwards for three decades now. But despite the varied themes of Edwards’ life I have addressed, and various contexts in which I have been asked to address them, at application time I continue to return to seven theses laid out in one of the books I wrote on Edwards aimed at pastors, Jonathan Edwards and the Ministry of the Word: A Model of Faith and Thought (IVP Academic, 2009). I share them with you today in honor of Edwards’ birthday (Oct. 5, 1703).

Thesis #1: Edwards shows us the importance of working to help people gain a vivid sense, an urgent impression, of God’s activity in our world.

As Christian witnesses in largely non- or post-Christian cultures, we should follow Edwards’ lead in striving creatively to stem the tide of unbelief and apathy. Naturalism and materialism pervade our world today. They even pervade our best churches. God is calling us, like Edwards, to combat these powerful trends, to enhance the faith of others in the reality, centrality, beauty, and practicality of God and divine things. Believe it or not, the Holy Spirit wants to use you in this way—in your culture and your church. Even in evangelical circles, Christian complacency is rampant. Edwards faced it more directly (as he worked in a state-church). But all of us struggle with it daily. As his ministry makes clear, moreover, this problem is treated effectively with faithful, learned, responsive, heart-felt, biblical theology, spiritual conversation, and “social religion.”

Thesis #2: Edwards shows us that true religion is primarily a matter of holy affections.

Christian doctrine is meant to be tasted, not just memorized, affirmed, and then debated with those who differ. God communicates with us in order to draw us near to him. He helps us grow in spiritual knowledge so we can grow in divine love. Head and heart must work together. “There is a difference between having an opinion that God is holy and gracious, and having a sense of the loveliness and beauty of that holiness and grace.” God reveals himself to us and dwells within us by his Spirit to inform, guide, and fashion our love for him and those around us.

Thesis #3: Edwards shows us the advantages of keeping an eschatological perspective on our lives.

The tyranny of the urgent and the pressure to “succeed” can thwart our Christian faith and practice. Keeping our minds on things eternal, though, can strengthen us for the day. As we remember God’s call on our lives, his larger purposes for our work, as well as his promise to sustain us, we are emboldened to be the people he created us to be. Those who trust in Scripture truth—who really believe in God and his Word—have less debilitating fear than most conventional “believers.” Conviction of the reality of heaven, hell, and eternity provides the kind of perspective that can keep priorities straight. Those who truly fear the Lord are free to act with holy boldness, to do the right thing whatever the cost (including the loss of livelihood and public humiliation).

Thesis #4: Edwards shows us how God uses those who lose their lives for Christ.

Those who live for themselves will lose themselves (Matt. 10: 39). But those who live for Christ, who die to themselves and cling to the cross, find themselves and their fulfillment in the One who loves them most. Edwards lived as a real martyr—a literal witness (Greek: martys) to his Lord—not a man with a martyr complex. He lived “with all his might” for “God’s glory” while he lived. He shows us how to get over ourselves. He teaches us to see our lives as part of God’s eternal plan to glorify himself through the redemption of the world. He certainly had his faults. In the end, though, he tried to let the Scriptures set the agenda for his daily life and ministry, refusing to make decisions out of inordinate self-concern.

Thesis #5: Edwards shows us that theology can and should be done primarily in the church, by pastors, for the sake of the people of God.

While this was easier to accomplish in his eighteenth-century world—before the professionalization of ministry and the specialization of disciplines—it remains a possibility today. In the early twenty-first century, when many pastors have abdicated their responsibilities as theologians, and many theologians do their work in a way that is lost on the people of God, we need to recover Edwards’ model of Christian ministry. Most of the best theologians in the history of the church were parish pastors. Obviously, however, this is not the case today. Is it any wonder, then, that many struggle to think about their daily lives theologically, and often fail to understand the basics of the faith? I want to be realistic here. A certain amount of specialization is inevitable in complex, market-driven economies. And the specialization of roles within God’s kingdom can enhance our Christian ministries. But when our pastors spend the bulk of their time on organizational matters, and professors spend their time on intramural academics, no one is left to do the crucial work of shaping God’s people with the Word. Perhaps our pastors and professors, Christian activists and thinkers, need to collaborate more regularly in ministry. Perhaps the laity need to give their pastors time to think and write—for their local congregations and the larger kingdom of God.

Thesis #6: Edwards shows us that even the strongest Christians need support from others.

Spiritual leaders need encouragement, advice, and accountability. Edwards knew this well, as did many of the Puritans. New England Congregationalists had independent churches. But their pastors met together for prayer, study, counsel, and fellowship. They were not lone rangers. They knew better than to strike out on their own.

Thesis #7: Edwards shows us the necessity of remaining in God’s Word.

Edwards spent the bulk of his time—nearly every day of his life—reading and meditating on Scripture. He believed his life and ministry depended on this practice. He understood the “importance and advantage” of theology. He taught that “every Christian should make a business of endeavoring to grow” in divine knowledge. He lived with the following truths emblazoned clearly on his life: “every one that useth milk is unskillful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil” (Heb. 5: 13-14). Would that all of us did the same, consuming a steady diet of “meat” and growing stronger in the Lord.

Douglas A. Sweeney is dean and professor of divinity at Beeson Divinity School. His most recent books on Edwards include Edwards the Exegete: Biblical Interpretation and Anglo-Protestant Culture on the Edge of the Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 2016), and The Oxford Handbook of Jonathan Edwards, co-edited with Jan Stievermann (Oxford University Press, 2021).