In a psalm attributed to Moses we are reminded, “Teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12). I like the rhythm of my days. I can’t complain. I have a pleasant mix of social interaction and a nice amount of people-time, as well as plenty of solitary study time. Back in the day, when we had three young kids to parent, a small church to pastor, and a full time teaching schedule to keep up with, the pace was pretty frenetic. But life has changed. I used to have more energy than time; but now I have more time than energy.

But this week we all began to face a new challenge, one that might stretch on for some weeks, maybe even months. To be honest that unsettles me. I like my schedule. I don’t like being homebound. I can’t read books all the time! And you can only watch so much CNN. The banality of TV reminds me of the Teacher’s assessment in Ecclesiastes. Netflix can be good. We watched “Driving Miss Daisy” last night, but every night doesn’t work. In the past I prided myself on having a farmer’s work ethic and maybe that’s what I need right now, a farm with chores and cows that don’t require social distancing and hands dirty with virus-free dirt.

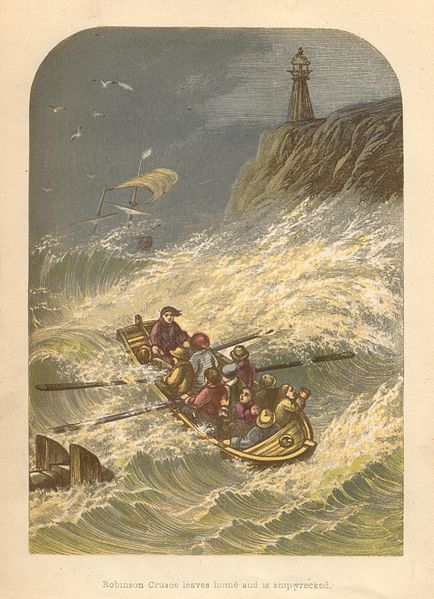

Moses’ admonition, “Teach us to number our days,” made me think of two works of art, the movie Castaway and the novel Robinson Crusoe. These two dramas explore the human trauma of time on our hands. In Castaway, Tom Hanks (who in real life has tested positive for COVID-19) plays Chuck Nolan, an efficiency expert for FedEx. His life consists of work and a relationship with a girlfriend. Just before he boards a FedEx flight to the South Pacific, he proposes to her. He kisses her goodbye and assures her he’ll be back in a week, but his plane goes down in a terrible storm and he washes up on a deserted island. He is the lone survivor and a modern day version of Robinson Crusoe. The differences between the movie Castaway and Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe illustrate the gap between survival and salvation and a modern scaled down view of life.

It is fitting that Castaway is a movie that looks at Chuck Nolan’s struggle to survive, while Robinson Crusoe is a novel that explores the mind and soul of Crusoe. The medium itself says something about the modern person. That is not to say that novels don’t depict a modern persona, but in the case of Robinson Crusoe, the novel captures his soul better than a movie could. In Castaway, we watch a familiar movie star act out a part. We comment to ourselves that Hanks looks heavy in the first half of the movie and about fifty pounds lighter in the second half of the movie. We make a mental note of his bleached hair and beard. From the odd assortment of FedEx packages that wash up on shore, we question the value of our materialism. We watch him try to build a fire out of rubbing sticks and extract a tooth with the tip of an ice-skate. The only real clues as to what was on his mind is his habit of looking at his girlfriend’s picture and his attempts to draw her likeness on the wall of a cave. When the body of the pilot washes up on shore, Nolan digs a shallow grave and buries the body. We see him standing before the mound, but instead of prayer, he comments, “That’s that.” The portrayal is entirely one-dimensional. It is a tale of survival. The greatest hint that he is a relational being comes in the humor and pathos of his conversations with Wilson, conceived when Nolan’s bloody hand print left a crude imprint of a face on a volley ball.

As the years drag on, Nolan contemplates suicide and becomes more like a caveman than a FedEx efficiency expert. He just barely clings to survival. Eventually, Nolan builds a raft and sails out to sea, to an almost certain death if it were not for the lucky break of being spotted by a tanker. After being gone for four years, he arrives home to find his fiancé married. He has survived, but he cannot redeem the lost years and the lost relationships. The movie closes with Nolan standing at a four-corner crossroads on the Texas panhandle as lost and directionless as he was on his deserted South Pacific island.

The contrast between Castaway and Robinson Crusoe could not be greater. In Defoe’s novel, Crusoe emerges from his nearly three decades of isolation a much stronger person in the end than he was at the beginning. His isolation proved invaluable. In the providence of God, his solitary life led him to examine himself. Suffering opened his heart and mind to God. Stripped of everything worldly, he saw himself as he really was, “without desire of good or conscience of evil.” He began to lament his “stupidity of soul” and his ingratitude to God. Illness led him to pray for the first time in years, “Lord be my help, for I am in great distress.” When he began to ask, “Why has God done this to me? What have I done to deserve this?”, his conscience checked him, “Wretch! Ask what you have done! Look back upon a dreadful misspent life and ask what you have done. Ask, why you have not been destroyed long before this!”

Robinson Crusoe is much more than a story about survival. It is a story about salvation. Like the prodigal son, who ran off to the far country, squandered his inheritance, but came to his senses, Crusoe became deeply convinced and convicted of his wickedness. When he earnestly sought the Lord’s help in repenting of his sins, he providentially came to the words in the Bible, “God exalted him to his own right hand as Prince and Savior that he might give repentance and forgiveness of sins to Israel” (Acts 5:31). He describes his reaction, “I threw down the book, and with all my heart as well as my hands lifted up to Heaven, in a kind of ecstasy of joy, I cried out aloud, ‘Jesus, Thou Son of David, Jesus, Thou exalted Prince and Savior, give me repentance!” Instead of praying for physical deliverance, he prayed for the forgiveness of his sins. Deliverance from sin was “a much greater blessing than deliverance from affliction.”

He came to the sober conclusion that the salvation of his soul meant far more to him than his deliverance from captivity. “...I began to conclude in my mind that it was possible for me to be more happy in this forsaken, solitary condition than it was probable I should ever have been in any other particular state in the world; and with this thought I was going to give thanks to God for bringing me to this place.” Instead of a slow and fearful descent into despair, Crusoe experienced God’s rhythms of grace. He read his Bible and prayed daily. He planted crops, made furniture, baked bread, built a canoe, and established an orderly, disciplined life. He lived a life of mercy, not sorrow, and his singular goal was to “make my sense of God’s mercy to me.”

The message of Castaway is that life is a struggle for survival fueled by the human spirit and the existential self. Love, particularly romantic love, can be a great motivator, but relationships are often disappointing and not enduring. Loneliness and isolation expose the myths of modern life, and in the end we are directionless. The message of Robinson Crusoe is that life is a struggle in our soul between self-rule and God’s will, and it can only come to resolution by the grace and mercy of God. Apart from the saving grace of the Lord Jesus Christ there is no hope, but with Christ we can experience an abundant life even in affliction and suffering.

Douglas D. Webster is professor of divinity at Beeson Divinity School, where he teaches Christian preaching and pastoral theology.