Time: December 1937-August 1939

Address: Majetki 3, Koszalin, Poland

After visiting Finkenwalde we drove 165 kilometers northwest to Mielno. This seaside town became our base for four nights as we joined Polish families on holiday. After a good rest and large breakfast at the hotel, on Tuesday, June 4 we set out for Koslin, a mere 20 kilometers away.

When the government closed Finkenwalde in September 1937, Bonhoeffer and the other Confessing Church seminary directors considered two choices. They could defy the ban and meet as before, or they could find a new approach. One seminary tried the former option and was closed down immediately. Bonhoeffer decided to use the format of the “collective pastorate,” a training program borrowed from small denominations without seminaries in which one or more students (collective) studied while living with a pastor and helping with ministry (pastorate). This training method was not technically illegal.

Unfortunately, this format has been constantly misunderstood in Bonhoeffer biographies. To summarize, there were two settings, not one. Students stayed in one location for four months, as they had in Finkenwalde. The format for life together was the same as in Finkenwalde. Students participated in local ministry, as they had in Finkenwalde. Each site had an associate director, as in Finkenwalde. The seminarians were not hiding out, for they served openly in congregations, some of them prominent ones. Because the places were smaller, they could not offer hospitality and do conference work, as they had in Finkenwalde. Also, Bonhoeffer had to split time at two sites.

Koslin, a city with a population of about 30,000, and Gross Schlonwitz, a village with about 400 inhabitants, became home to the seminaries. Two district Superintendents pastoring prominent St. Mary churches welcomed them: Eduard Block (Schlawe) and Friedrich Onnasch (Koslin). Bonhoeffer assigned two men who had been with him since Zingst to lead the work: Eberhard Bethge in Gross Schlonwitz and Fritz Onnasch in Koslin.

Writing to former seminarians on March 14, 1938 Bonhoeffer observed that “Fritz and Eberhard have much to do and much joy in their work. Some things are different and more difficult, but others are more pleasant” (DBWE 15:40).

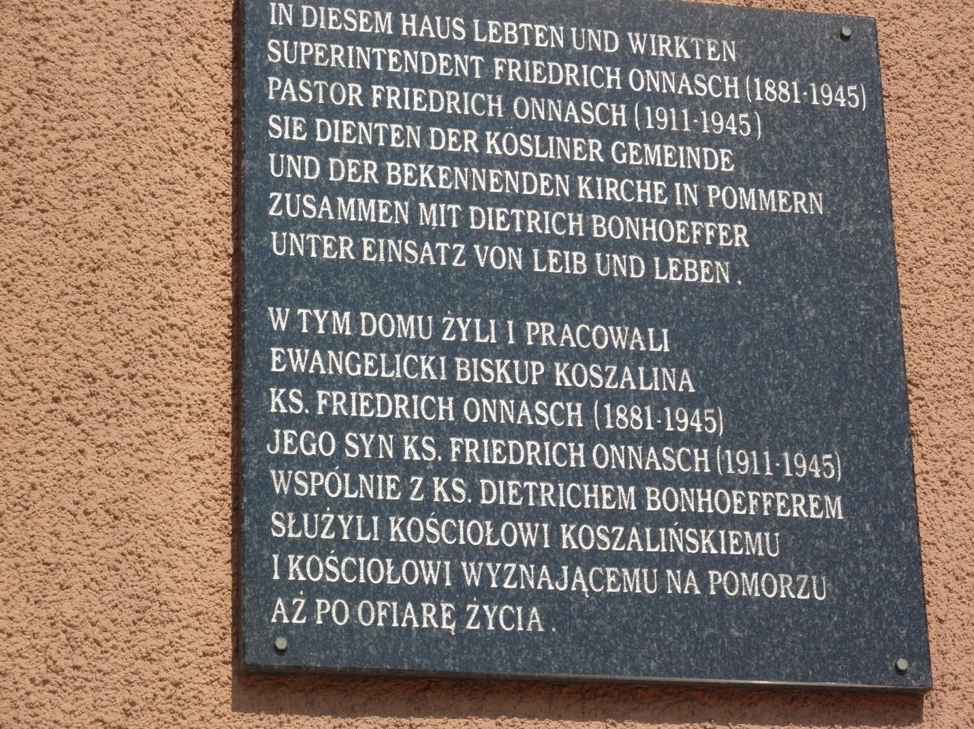

No seminary marker exists in Koslin. However, Bonhoeffer and the seminarians lived and studied in Friedrich Onnasch’s home, which included administrative and educational space. The building no longer stands, but on the three-story building now on the site there is a plaque that honors Friedrich and Fritz Onnasch and notes their association with Bonhoeffer.

Of the five Bonhoeffer seminary sites, Koslin is probably the least known. Though Bonhoeffer was a guest preacher there in 1936 and probably afterwards, no Koslin manuscript sermon is in the Bonhoeffer Works in English. Few of Bonhoeffer’s extant letters were sent from Koslin. Notes from the pastoral theology lectures Bonhoeffer gave there have survived, but little else as far as documents go. What has survived and deserves more attention is the witness of Friedrich and Fritz Onnasch.

After he finished his studies, Fritz Onnasch became Finkenwalde’s house manager, devoting many hours to administrative and hospitality matters. He was also assistant pastor of a congregation two kilometers away. While serving this church, the government imprisoned him from November 18-December 20, 1937. Thus, he took up the seminary work immediately upon leaving jail. In September 1939, Fritz married Eberhard Bethge’s sister Margret. Fritz served the Confessing Church throughout the war. Childhood polio shielded him from conscription. Eberhard Bethge called him “imperturbable.”

Friedrich became pastor of St. Mary’s Church and District Superintendent in 1922. The church spire is prominent in many photographs of the time. Now a Catholic church again, the building still has large stained-glass windows featuring Luther and Melanchthon.

Friedrich Onnasch was a fearless preacher and leader. For example, in September 1939 he was jailed for preaching a sermon that questioned the morality of the new war. He ministered to Catholics and communists, not just Protestants. He performed Fritz and Margret’s wedding while on a weekend pass from prison. The government banished Friedrich from Koslin in 1940. He settled in Berlin and served as a pastor. Soviet troops conquering Berlin shot him in 1945.

Fritz died in the family home, the former seminary site, on March 4, 1945. Fritz, Margret, and their three children were hiding in the basement. The Soviet army was seeking revenge on all Germans. Fritz went upstairs to heat milk for their nine-month-old son. Soviet soldiers shot him in the kitchen and left him there. His wife and children found him two days later. He was buried nearby, but the site has been lost.

Bonhoeffer was wise to pick Fritz to lead the Koslin group in Friedrich’s district. As events proved, the Onnaschs did not scare, they would not quit, they resisted the government and the compromised church, and they left a witness worth learning. Our job is to learn and remember, to confess and to remind ourselves and others of full-grown faithfulness. Koslin reminded me that many of Bonhoeffer’s friends were extraordinary.