Beeson Divinity School has had a close connection to Dietrich Bonhoeffer from its inception. The inaugural class penned a covenant defining the community’s life together in terms similar to those Bonhoeffer and his seminarians shared. Of the six busts of martyrs in Hodges Chapel, Bonhoeffer represents Europe. Beeson has focused on Bonhoeffer, Barmen and related Confessing Church subjects in chapel series. At least three current Beeson professors have written books on Bonhoeffer. Seminars on Bonhoeffer and his historical context have been offered in January terms. The annual all-seminary retreat has been named Finkenwalde Day. And you are reading Finkenblog.

For reasons I have given in some detail elsewhere, I find this focus appropriate. Personally, I have been reading and learning from Bonhoeffer for forty years. His work as a Confessing Church pastor, theologian, seminary director and theologian-at-large during 1933-42 offer me a challenging ministry model.

After writing about Bonhoeffer’s seminary vision, I wanted to see the places where this work occurred. After all, people and places join theological convictions and educational methods in shaping pastoral formation. I felt I needed some more local context to grasp how Bonhoeffer can continue to help shape Beeson and other face-to-face seminaries, especially ones in mission settings.

I am grateful that Beeson Divinity School, Samford University and the Heather House Trust made it possible for me to spend June 1-8 in Germany and Poland visiting Bonhoeffer’s five seminary sites: Zingsthof, Finkenwalde, Köslin, Gross Schlonwitz and Sigurdshof. The journey also made it possible to stop at Bonhoeffer’s last home in Berlin, where Bonhoeffer kept an official address, and Kikowo (Tychowo), where Bonhoeffer preached a confirmation sermon on April 9, 1938, and spent time with the woman who eventually became his fiancée. The terrain and population density showed that Bonhoeffer’s approach to seminary work could flourish in resort towns (Zingst), suburbs (Finkenwalde), large towns (Köslin), hamlets (Gross Schlonwitz) and completely rural settings (Sigurdshof).

The trip was made richer by the companionship, driving and German skills of my friend Scott Hafemann. Scott had already been in Germany for a week attending a conference when I arrived. Friendship was quite important to Bonhoeffer and is quite important to me and to Scott. Our conversations and his spontaneous observations enriched the time. His fluency in German and his accidental renting of a car with a fine GPS system were crucial to finding some of the more obscure places and to taking advantage of some unexpected opportunities.

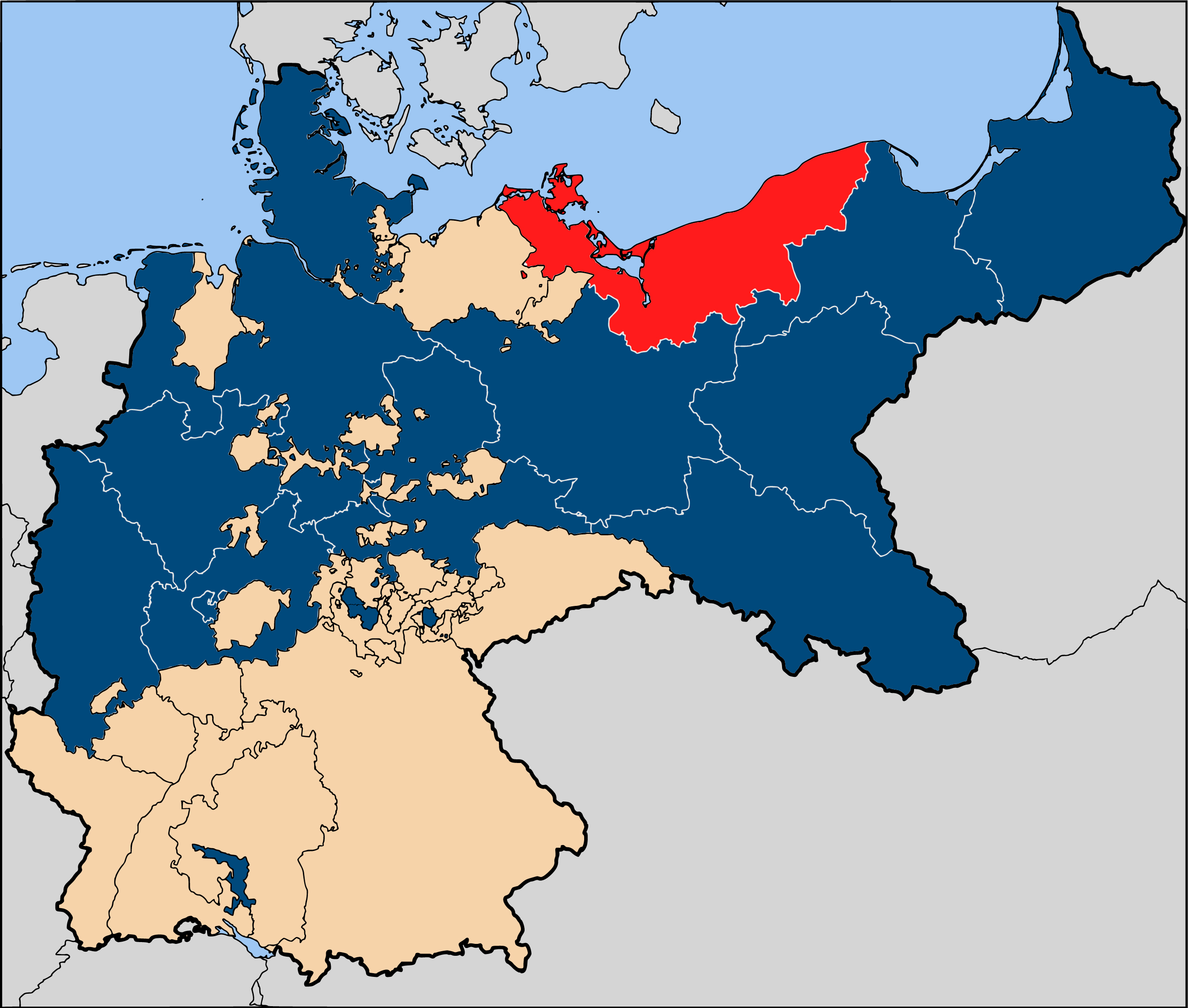

It is extremely important to understand that Bonhoeffer’s seminaries served Pomerania. Confessing Church seminaries were located in other regions. In the 1930s, Pomerania included part of what is northeast Germany today and what is now northwest Poland. Since the war began in September 1939 when Germany and Russia invaded Poland, Pomerania always had lots of military personnel and multitudes of refugees. When the Red Army smashed west towards Berlin after 1942, more refugees fled through Pomerania. Hundreds of thousands died, including some of Bonhoeffer’s close friends.

When the Soviets conquered Pomerania, they drove millions of Germans beyond the Oder River and eventually replaced the population with Poles. Formerly German cities received Polish names. Thus, Stettin became Szczecin, and Finkenwalde was incorporated into that city and is now the suburb Zdroje. Koslin became Koszalin, Gross Schlonwitz became Slonowice, and the von Kleist estate near Tychowo where Sigurdshof was located became a collective farm. Street names changed as well, complicating parts of our visit.

Finally, many Protestant church buildings were given to the Catholic church. Or, as Catholics might point out, they were given back to the Catholic church, many having been taken from Catholics by Protestants during the Reformation. Pomerania has been a scarred land for a long time. The fall of the Soviet Empire was just the most recent major geopolitical change.

Again, places matter. Their people and their history teach attentive people. Scott and I hoped to be attentive. There was much we saw that we could not grasp fully. Yet we knew that if Bonhoeffer’s seminary ministry bore fruit in a contested land that Beeson has been right to use it as a yardstick for its own ministry.