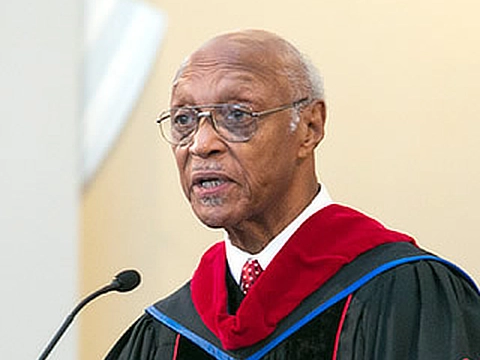

Given by the late James Earl Massey on February 14, 1998, to the faculty of Beeson Divinity School on the school’s 10th anniversary.

As we gather here, I am thinking about the fact that we have spent most of our years in schools; we were first taken to school as children, but we chose in time to stay in school on our own, lured by learning, and eager to gain what would make us valuable within some setting as scholar-teachers. I speak here without regret as I say that educational institutions have long been my second home, and all the schools I attended are a major part of the environment that helped to form my identity and determine my readiness for life. Schools are central entities in shaping our vision, our values, and, considering our kind of school, even human destiny.

While preparing for this retreat I thought about my debt to the schools that blessed me with what they had to offer. I thought about what I have taken with me from my encounters with able teachers and associations with fellow students. As I thought back on it all, I was quite mindful of how we who teach tend to romanticize the past and sometimes seek to repeat some of the past. I say this because any walk down memory lane must always be made with some awareness that biases and preferences are usually at work as we move along; we bring with us on that journey some sentiments which skew perspectives at times, and we must be reminded that the places we remember are no longer the same as when we knew them, nor are we the same now as we were then. I say this, also, because having been influenced to some extent by the cultures reflected in the schools we attended and remember, we are sometimes tempted to try and reduplicate those cultures in what we do and dream now, and those sentiments can sometimes make us unsympathetic to the setting in which we must do our work now. As you plan and project here for the next leg of your institutional journey, I trust that you will avoid this by all means!

For ten years now, you have been "Beeson Divinity School" of Samford University. You have become a particularized faculty, guided by stated institutional goals and church relationships. You serve within a distinct historical setting and are housed in a matchless set of physical facilities. (I know of no other school which has had the distinct privilege of starting, as you did, with such auspicious benefits and backing!) You have done your work with such quality and steadiness that you have three accredited graduate degree programs as your province and you have an ever-changing but quality student mix as prime beneficiaries of what you have planned and are carrying out in action. While here, you have been engaged m reviewing your course. I trust that you have also experienced re-visioning as you have thought and prayed about your work. Your teaching and curricular matters reflect a tradition that has been developing in your school; they relate to your ongoing history, and they must extend and enhance that history in a manner necessary for another time and group. Duly value your history, however brief it seems, and learn from it, however limited it be, as you make revisions for your future.

Simply stated, as a divinity school, a seminary of and for the church, your academic task is planning and teaching such courses and supervising such fieldwork that is crucial to the making of ministers. Your concern must ever be to make ready those who come to you seeking to become "able ministers" in the cause of Christ and church. Success in helping them to become what their calling opens to them demands so much more than what you have to offer: it demands the enabling Hand of God upon them, as upon you; it demands a steady commitment to God by them, as by you; it requires a surrender of the giftedness that nature and God have provided them, and you; and it requires the trust of the church by which opportunities for service and growth can occur for you and for them. All this is surely involved, but for now we are mindful of your part in their shaping, and the need to remain true to what the Lord entrusts you to be, and faithful to what the church supports you to do, in the making of ministers.

Upon graduating from the University of Berlin, where his studies with Adolf von Harnack, Karl Holl, and Reinhold Seeberg, among others, equipped him theologically for his ministry, Dietrich Bonhoeffer expressed gratitude to his teachers by writing some phrases of farewell to them on his thesis. He wrote this to Professor Harnack: "What I have learnt and come to understand in your seminary is too closely associated with my whole personality for me to be able ever to forget it."[1]

Two years later, during the Summer of 1929. the young Bonhoeffer and some of his friends attended a farewell event honoring the eighty-seven-year-old Harnack. In his tribute to Harnack on that occasion, Bonhoeffer said: "That you were our teacher for many hours was a passing thing; that we can call ourselves your pupils remains."[2]

These stirring tributes were to one who honorably bore the teacher's yoke. For those of us entrusted with the blessed privilege to teach, such tributes keep us mindful that a crown of trust has been placed above our heads and we must continually grow taller if we are ever to reach it.

Teaching is indeed a privileged work. It is a fundamental activity filled with promise. Jacques Barzun made the timely and strategic reminder that the task of teaching is to turn pupils into lifelong learners, aiding them to be creative and productive persons, and his comment highlights distinct aspects of that promise.[3] This process of assisting students to become independent learners is usually prolonged and sometimes painful. It means interacting with students who alternate in their attitudes toward us: they openly receive us for a while, then they stand off in rejection; usually they trust us but often test us; they are curious and eager to know most of the time, but they are sometimes hampered by resentment toward the demands we place upon them in the process to discover and understand, recall matters, and relate those matters for the meaning they hold or suggest. Near the end of his long and illustrious teaching career, William James was probably recalling how this sometimes-distressing process had weighed upon him when he rejoiced aloud that, having retired, he would no longer have to face a "mass of alien and recalcitrant humanity. "[4] Teaching is a difficult task, but the difficulties are because of the promise associated with it, the promise of life-changing benefits to growing persons.

Good teaching involves far more than the airing of facts and the concern to stimulate inquiry; it also involves an understanding of students as persons, and the need to honor their human worth. As you well know, a wide range of activities are necessary to the task of teaching, activities such as reading, research, reflection, consultation with one's colleagues, modeling virtues and skills, promoting values, mapping the process and monitoring the progress of students in relation to a course and a prescribed curriculum, but central to our work is the spirit in which we do all of these. Along with the other benefits that our learning and scholarly process equip us to share with them, students need our human touch. Gilbert Highet had this in mind when he advised that to teach well, "You must throw your heart into it, and must realize that it cannot all be done by formulas, or you will spoil your work, and your pupils, and yourself. "[5]

In 1897 the book Men I Have Known was published. It was written by clergyman Frederick W. Farrar, and in it he reminisced about eminent persons he had known. Poet Robert Browning was one of them, and Farrar quoted a comment Browning once made to him about how important it is that young people have the memory of "seeing great men." I thought of that comment while preparing this address to you, because among the many memories I have of my grade school years there is the memory of a good and great teacher, my most unforgettable teacher, an African American man who threw his heart and life into the then-awesome task of teaching me. He was learned, gifted, competent, diligent, focused, industrious, and caring. His name was Coit Cook Ford, Sr.

Mr. Ford's classroom was a virtual picture gallery, and as he taught us he supplemented the textbook materials with information about the persons whose glossy photographs lined the space between the ceiling and the blackboard along the classroom walls. I shall never forget the drama we children sensed as Mr. Ford involved us in those vivid and valuable stories. The stories impacted our imagination and made us dare to dream, because each hearing deepened our sense of identity and confidence in ourselves because the pictures on the walls were of African Americans who were grand achievers, persons who despite great odds had become great. Mr. Ford knew what we would face growing up black in America, and he addressed that need. But he also knew our need to wed discipline and courage to the pride and hope deepening in us, so he soberly advised us with some lines that I later discovered were from Longfellow's poem "The Ladder of Saint Augustine'':

The heights by great men reached and kept

Were not attained by sudden flight;

But they, while their companions slept,

Were toiling upward in the night.

Those lines, which I heard for the first time at Ulysses S. Grant Grade School in Ferndale, Michigan, still stir my spirit and prod me to be diligent in every quest and endeavor. Mr. Ford's informative, insightful, and caring classroom work marked me at deep levels within. It should be no wonder, then, why teaching came to stand out in my mind as such a noble work.

A few years ago, I joined with other friends, family members, and former students of Mr. Ford to attend his funeral service in Detroit. He and I had remained close across the years, sharing letters, telephone calls, and visits from time to time. He died in his ninety-third year of life, and we had conversed by phone during the month before his death. Mr. Ford's last letter to me is now among my most treasured materials, for with it he sent a list of former students with whom he was still in contact, and beside each name on the list was a brief description of what that person was currently doing. He had also enclosed a gift photograph of himself taken when he was my grade schoolteacher! That memento holds deep meaning for me, and it keeps me reminded that the central issue in both teaching and living is to touch other lives in meaningful ways. Good teaching happens not only when essential information is shared and inspiration is gained but when a good human influence is experienced. This is the kind of teaching that deserves to prosper. It is not incidental that the great leaders in history, religious leaders included, have been teachers!

Some moments ago I quoted Dietrich Bonhoeffer's tribute to Harnack as a teacher; I must now mention something else Bonhoeffer wrote about his teachers.

Writing from Tegel Prison to his parents on Reformation Day, 1943, seven months into his confinement there because of his political resistance against Hitler, Bonhoeffer was still aware of the rhythm of the church year and shared with them some of his meditation about the meaning of that day. He also shared his wonderment about why Martin Luther's actions and teachings had been followed by consequences which were the· exact opposite of what he had intended.[6] Luther had worked for unity between Christian people, but both the church and Europe had been torn apart. He had worked for the "freedom of the Christian believer," but the unexpected consequence was licentiousness among the masses. Luther had worked to bring about a secular order freed from clerical privilege and control, but the result was insurrection, the Peasant's War, and general disorder in society. Luther was so affected by the surprising turn of events that his last years of life were tormented; again and again he doubted the value of his life's work. Bonhoeffer thought about all this on that Reformation Day, and he remembered a classroom discussion in Berlin when Karl Holl and Adolf von Harnack debated whether the great historical intellectual and spiritual movements made headway through their primary or their secondary motives. Holl had argued that such movements went forward due to their primary motives, while Harnack countered that the secondary motives moved them forward. While hearing them debate, Bonhoeffer had thought Holl was right and that Harnack was wrong. But later, in prison, reflecting on what had happened to Germany under Hitler, and on his own situation as a political prisoner, Bonhoeffer was inclined to think that Harnack was right in insisting that historical movements move forward more persistently by secondary motives.

I have mentioned this report from Bonhoeffer's meditational assessment of history because as a history-making action our teaching, however well prepared and adroitly handled, and however bright the students engaged by it, involves us in a circle of circumstance, and we must approach our task tempered by an understanding that much of what we intend as we teach will not happen as intended, that much of what we do will bear consequences we did not intend to effect. Some of what we teach out of a primary motive will fall short of our intended purpose because of circumstance, and some secondary effect will become prominent. This conditional factor of circumstance should keep us reminded that what we are as we teach is as crucial to our work as what we know and what we do with what we know. The fact that circumstance will affect our work should also keep us sensitive to the need for help from beyond ourselves as we teach. As one who teaches, I have found this prayer-plea voiced in Psalm 90, and credited to Moses, a teaching leader, a necessary and ready encouragement: "Let the favor of the Lord, our God, be upon us; and prosper for us the work of our hands — O prosper the work of our hands!” (90:17).

Across ten years now, since 1988, students have been coming to you with an interest that you assist them to become trained servants for ministry. They have come to you with their eagerness, with their questions, with their dreams, with their differences, their needs—and their potential. You have had much to give, and you have been giving it. Many have gone from your hallowed halls blessed with needed perspective, theological focus, personal convictions, devotional earnestness, evangelical passion, and a strong service motive, and they have thrust themselves into their work with creativity, gratitude and gusto. With you, I glorify God for his faithfulness to you as you did your work with them.

Others will come to you, seeking what you have to help them become a blessing to the church and the world. Knowing you as I do, I am confident that you will return to your work spiritually renewed, eager to continue the scholarly and spiritual pursuits to stay fresh for your task. Continue, then, your emphasis on teaching. Honor the framework of meaning that encases what you have been doing, and continue to work with a conscious focus as you assist the learning process of those who look to you. Believingly trust that there is a future to what you do, a God-honoring future. Give yourselves to deeper study, prolonged thought, steady planning, unflinching discipline, unceasing prayer, persistent work, and patience, doing what is your's to do, but trusting God to bless it all to the highest good. As you are being lured by the future, continue learning from your past, with the cross of Jesus as the sign and seal always in your view.

I close with this choice statement from H. Wheeler Robinson, the famed principal and professor of Regent's Park College, Oxford, earlier in this century: "The way in which a man begins a job shows what he will do with it; the way he finishes it shows what it has done with him."

Footnotes

[1] See Eberhard Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), p. 46. Eng. trans. by Eric Mosbacher, er al., under the editorship of Edwin Robertson.

[2] Ibid., p. 102.

[3] See Jacques Barzun, Teacher in America (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., Inc., 1959), esp. pp. 17-3 I.

[4] Cited by Barzun. p. 31.

[5] The Art of Teaching (New York: Vintage Books, 1961), p. viii.

[6] See Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers From Prison: Enlarged Edition, edited by Eberhard Bethge (New York: Macmillan Publishig Co., 1972).