In 1979, Samford professor Marlene Rikard led a class of students in an oral history project centered around the coal mining town of Docena, Alabama. In 2018, the Samford Oral History program worked with Samford Special Collection to restore these interviews, converting audio reels to mp3 files and typewritten transcripts to digital documents to share these remarkable stories with the public.

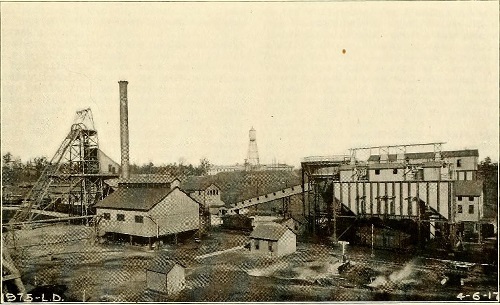

Only a few miles northwest of downtown Birmingham, Docena was a company town run by the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company from the 1910s to the 1950s. The mines closed permanently in the early 1960s, leaving Docena in a decline. In these interviews, seven members of the Docena community recall their experiences in the town during its coal mining boom and offer insight into the changes, good and bad, that they have witnessed in their community.

More interviews from Dr. Rikard’s 1979 project are available in Samford Special Collection.

Language Analysis Summary

A summary of some of the findings from a linguistic analysis of seven TCI interviews.

B.D. Oglestree

"Put it in the cart, run it on through, a lot of improvement. Kinda like it is now. You mash a button on it now. You used to have to get it. A man’s strength."

Christine Cochran

"Yes, I think that we are closer together because we shared our hardships together. And when it eased off, we’re still sharing together. If a house gets burned up, we all just put together and soon we have them started again. So, we use a lot of togetherness because in the times of hardship and tribulation, we had to be together—the only way of surviving."

E.L. McFee

"These people were very likable, hard-working, and that’s hard work, dangerous living. They felt pretty close to each other. They helped each other, somebody in the community got in trouble, then food, whatever was needed, the whole community rallied in that direction."

Samuel Kelley and James Simmons

". . . we had an athletic program here. Our baseball team was as good as any. The Black Barons were known then and we played them twice and they didn’t beat us. We did, we had a third game scheduled, but they didn’t want to be bothered with the miners (laughs) see."

The following is an excerpt of a longer interview with Mr. Kelley and Mr. Simmons. The full transcript for this interview can be accessed in Samford Special Collection.

Melba Wilbanks Kizzire and Edna Mae Plunkett

". . . well coal miners are coal miners at heart, wherever they are. They're facing danger every day, so it brings them closer together."

Mary Parsons Gray

"It, it has changed, the whole thing has changed now. Now it is, I don't think people, they realize the importance of [coal mining], and they realize that people are, um, who live there are like everybody else. And uh, but I had a feeling when I was growing up that it was, uh, that you had to defend it."

W.T. Turner

"I quit school and over my father’s objections I kept on till I got a job in the mines, and he was assistant superintendent in charge of the night shift. He could get me a job if we wanted to, but he didn’t want me in the mine, but he finally gave in and gave me a job loading coal 42 cents a ton and they put me in a water hole and made just as hard as they could possible make on me, so that maybe I would quit and come back out. But I didn’t. "